The Age of Pilgrimages Romanesque Art What Is It Meant by the Whote Robe of Churches

Romanesque fine art is the art of Europe from approximately yard AD to the rise of the Gothic style in the twelfth century, or afterward depending on region. The preceding period is known every bit the Pre-Romanesque period. The term was invented by 19th-century fine art historians, especially for Romanesque architecture, which retained many basic features of Roman architectural mode – most notably round-headed arches, only also barrel vaults, apses, and acanthus-leaf decoration – merely had too developed many very different characteristics. In Southern France, Spain, and Italia in that location was an architectural continuity with the Tardily Antiquarian, but the Romanesque way was the beginning manner to spread across the whole of Catholic Europe, from Sicily to Scandinavia. Romanesque fine art was also greatly influenced past Byzantine art, especially in painting, and by the anti-classical energy of the ornament of the Insular art of the British Isles. From these elements was forged a highly innovative and coherent style.

Characteristics [edit]

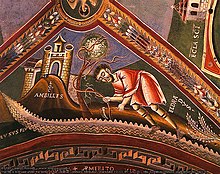

Outside Romanesque architecture, the art of the menstruum was characterised by a vigorous fashion in both sculpture and painting. The latter continued to follow essentially Byzantine iconographic models for the virtually mutual subjects in churches, which remained Christ in Majesty, the Final Judgment, and scenes from the Life of Christ. In illuminated manuscripts more than originality is seen, every bit new scenes needed to be depicted. The most lavishly decorated manuscripts of this period were bibles and psalters. The same originality applied to the capitals of columns: often carved with complete scenes with several figures. The big wooden crucifix was a High german innovation at the very start of the catamenia, as were gratis-standing statues of the enthroned Madonna. Loftier relief was the dominant sculptural mode of the catamenia.

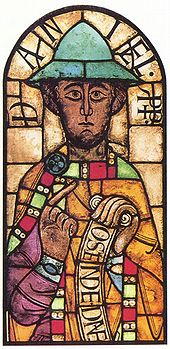

Colours were very striking, and more often than not primary. In the 21st century: these colours can only exist seen in their original brightness in stained glass, and a few well-preserved manuscripts. Stained glass became widely used, although survivals are sadly few. In an invention of the catamenia, the tympanums of important church building portals were carved with monumental schemes, often Christ in Majesty or the Last Judgement, only treated with more than liberty than painted versions, as there were no equivalent Byzantine models.

Compositions usually had niggling depth and needed to exist flexible to be squeezed into the shapes of historiated initials, column capitals, and church tympanums; the tension between a tightly enclosing frame, from which the composition sometimes escapes, is a recurrent theme in Romanesque art. Figures oft varied in size in relation to their importance. Landscape backgrounds, if attempted at all, were closer to abstract decorations than realism – as in the copse in the "Morgan Leaf". Portraiture hardly existed.

Background [edit]

During this period Europe grew steadily more than prosperous, and fine art of the highest quality was no longer confined, as information technology largely was in the Carolingian and Ottonian periods, to the royal courtroom and a small circle of monasteries. Monasteries continued to exist extremely of import, specially those of the expansionist new orders of the period, the Cistercian, Cluniac, and Carthusian, which spread beyond Europe. But city churches, those on pilgrimage routes, and many churches in small-scale towns and villages were elaborately decorated to a very loftier standard – these are often the structures to accept survived, when cathedrals and city churches have been rebuilt. No Romanesque royal palace has really survived.

The lay artist was becoming a valued effigy – Nicholas of Verdun seems to accept been known across the continent. About masons and goldsmiths were now lay, and lay painters such every bit Master Hugo seem to have been in the majority, at to the lowest degree of those doing the best work, past the stop of the period. The iconography of their church building piece of work was no doubt arrived at in consultation with clerical advisors.

Sculpture [edit]

Metalwork, enamels, and ivories [edit]

Precious objects in these media had a very high condition in the menses, probably much more so than paintings – the names of more makers of these objects are known than those of contemporary painters, illuminators or builder-masons. Metalwork, including ornament in enamel, became very sophisticated. Many spectacular shrines made to hold relics have survived, of which the best known is the Shrine of the Three Kings at Cologne Cathedral by Nicholas of Verdun and others (c. 1180–1225). The Stavelot Triptych and Reliquary of St. Maurus are other examples of Mosan enamelwork. Large reliquaries and altar frontals were congenital around a wooden frame, but smaller caskets were all metal and enamel. A few secular pieces, such as mirror cases, jewellery and clasps have survived, but these no doubt under-represent the amount of fine metalwork owned by the nobility.

The bronze Gloucester candlestick and the brass font of 1108–1117 at present in Liège are superb examples, very different in style, of metal casting. The former is highly intricate and energetic, drawing on manuscript painting, while the font shows the Mosan style at its most classical and majestic. The bronze doors, a triumphal column and other fittings at Hildesheim Cathedral, the Gniezno Doors, and the doors of the Basilica di San Zeno in Verona are other substantial survivals. The aquamanile, a container for water to wash with, appears to have been introduced to Europe in the 11th century. Artisans often gave the pieces fantastic zoomorphic forms; surviving examples are mostly in brass. Many wax impressions from impressive seals survive on charters and documents, although Romanesque coins are mostly non of swell aesthetic interest.

The Cloisters Cross is an unusually large ivory crucifix, with complex etching including many figures of prophets and others, which has been attributed to one of the relatively few artists whose name is known, Master Hugo, who also illuminated manuscripts. Like many pieces it was originally partly coloured. The Lewis chessmen are well-preserved examples of small ivories, of which many pieces or fragments remain from croziers, plaques, pectoral crosses and like objects.

Architectural sculpture [edit]

With the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the tradition of etching large works in rock and sculpting figures in statuary died out, as information technology effectively did (for religious reasons) in the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) world. Some life-size sculpture was evidently done in stucco or plaster, just surviving examples are understandably rare.[1] The best-known surviving large sculptural work of Proto-Romanesque Europe is the life-size wooden Crucifix deputed by Archbishop Gero of Cologne in almost 960–965, apparently the prototype of what became a popular form. These were afterward fix up on a beam below the chancel arch, known in English as a rood, from the 12th century accompanied by figures of the Virgin Mary and John the Evangelist to the sides.[2] During the 11th and 12th centuries, figurative sculpture strongly revived, and architectural reliefs are a hallmark of the later on Romanesque period.

Sources and mode [edit]

Figurative sculpture was based on two other sources in particular, manuscript illumination and modest-scale sculpture in ivory and metal. The extensive friezes sculpted on Armenian and Syriac churches have been proposed as another likely influence.[three] These sources together produced a singled-out style which can be recognised across Europe, although the most spectacular sculptural projects are concentrated in S-Western France, Northern Espana and Italia.

Images that occurred in metalwork were frequently embossed. The resultant surface had two chief planes and details that were usually incised. This treatment was adjusted to stone carving and is seen particularly in the tympanum in a higher place the portal, where the imagery of Christ in Majesty with the symbols of the Four Evangelists is drawn directly from the gilt covers of medieval Gospel Books. This style of doorway occurs in many places and continued into the Gothic flow. A rare survival in England is that of the "Prior's Door" at Ely Cathedral. In South-Western France, many have survived, with impressive examples at Saint-Pierre, Moissac, Souillac,[4] and La Madeleine, Vézelay – all daughter houses of Cluny, with extensive other sculpture remaining in cloisters and other buildings. Nearby, Autun Cathedral has a Final Sentence of great rarity in that it has uniquely been signed past its creator, Giselbertus.[5] [6]

A feature of the figures in manuscript illumination is that they oftentimes occupy confined spaces and are contorted to fit. The custom of artists to brand the effigy fit the available infinite lent itself to a facility in designing figures to ornament door posts and lintels and other such architectural surfaces. The robes of painted figures were commonly treated in a flat and decorative manner that bore lilliputian resemblance to the weight and fall of actual cloth. This characteristic was besides adapted for sculpture. Among the many examples that exist, 1 of the finest is the figure of the Prophet Jeremiah from the colonnade of the portal of the Abbey of Saint-Pierre, Moissac, France, from about 1130.[vi]

I of the most pregnant motifs of Romanesque design, occurring in both figurative and non-figurative sculpture is the spiral. I of the sources may exist Ionic capitals. Scrolling vines were a common motif of both Byzantine and Roman design, and may be seen in mosaic on the vaults of the 4th century Church building of Santa Costanza, Rome. Manuscripts and architectural carvings of the twelfth century take very similar scrolling vine motifs.

This capital of Christ washing the anxiety of his Apostles has strong narrative qualities in the interaction of the figures.

Another source of the spiral is conspicuously the illuminated manuscripts of the 7th to 9th centuries, especially Irish manuscripts such as the St. Gall Gospel Book, spread into Europe past the Hiberno-Scottish mission. In these illuminations the use of the screw has zip to do with vines or other constitute forms. The motif is abstruse and mathematical. The style was then picked up in Carolingian art and given a more botanical character. It is in an adaptation of this form that the spiral occurs in the draperies of both sculpture and stained glass windows. Of all the many examples that occur on Romanesque portals, one of the most outstanding is that of the cardinal figure of Christ at La Madeleine, Vezelay.[half dozen]

Another influence from Insular art are engaged and entwined animals, frequently used to superb effect in capitals (as at Silos) and sometimes on a column itself (as at Moissac). Much of the treatment of paired, confronted and entwined animals in Romanesque decoration has like Insular origins, as practice animals whose bodies tail into purely decorative shapes. (Despite the adoption of Hiberno-Saxon traditions into Romanesque styles in England and on the continent, the influence was primarily 1-way. Irish art during this catamenia remained isolated, developing a unique amalgam of native Irish gaelic and Viking styles which would be slowly extinguished and replaced past mainstream Romanesque style in the early on 13th century following the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland.[7])

Subject matter [edit]

Most Romanesque sculpture is pictorial and biblical in subject. A nifty variety of themes are found on capitals and include scenes of Creation and the Autumn of Homo, episodes from the life of Christ and those Former Testament scenes which prefigure his Decease and Resurrection, such as Jonah and the Whale and Daniel in the lions' den. Many Nativity scenes occur, the theme of the Three Kings being particularly pop. The cloisters of Santo Domingo de Silos Abbey in Northern Kingdom of spain, and Moissac are fine examples surviving complete, as are the relief sculptures on the many Tournai fonts establish in churches in southern England, France and Kingdom of belgium.

A feature of some Romanesque churches is the extensive sculptural scheme which covers the surface area surrounding the portal or, in some case, much of the facade. Angouleme Cathedral in France has a highly elaborate scheme of sculpture set within the broad niches created by the arcading of the facade. In the Spanish region of Catalonia, an elaborate pictorial scheme in depression relief surrounds the door of the church building of Santa Maria at Ripoll.[6]

Around the upper wall of the chancel at the Abbaye d'Arthous, Landes, France, are small figures depicting animalism, intemperance and a Barbary ape, symbol of human depravity.

The purpose of the sculptural schemes was to convey a message that the Christian believer should recognize wrongdoing, apologize and be redeemed. The Last Judgement reminds the believer to repent. The carved or painted Crucifix, displayed prominently within the church, reminds the sinner of redemption.

Often the sculpture is alarming in form and in bailiwick thing. These works are found on capitals, corbels and bosses, or entwined in the foliage on door mouldings. They correspond forms that are not easily recognizable today. Mutual motifs include Sheela na Gig, fearsome demons, ouroboros or dragons swallowing their tails, and many other mythical creatures with obscure meaning. Spirals and paired motifs originally had special significance in oral tradition that has been lost or rejected by modern scholars.

The Seven Deadly Sins including lust, gluttony and avarice are also often represented. The advent of many figures with oversized genitals can be equated with carnal sin, so tin can the numerous figures shown with protruding tongues, which are a characteristic of the doorway of Lincoln Cathedral. Pulling one'due south bristles was a symbol of masturbation, and pulling one's rima oris wide open up was also a sign of lewdness. A common theme establish on capitals of this catamenia is a tongue poker or bristles stroker existence beaten by his wife or seized by demons. Demons fighting over the soul of a wrongdoer such as a miser is another popular discipline.[8]

Pórtico da Gloria, Santiago Cathedral. The colouring once mutual to much Romanesque sculpture has been preserved.

Late Romanesque sculpture [edit]

Gothic architecture is normally considered to begin with the design of the choir at the Abbey of Saint-Denis, north of Paris, by the Abbot Suger, consecrated 1144. The beginning of Gothic sculpture is usually dated a little afterward, with the carving of the figures around the Royal Portal at Chartres Cathedral, France, 1150–1155. The mode of sculpture spread rapidly from Chartres, overtaking the new Gothic architecture. In fact, many churches of the late Romanesque flow mail service-date the building at Saint-Denis. The sculptural style based more upon observation and naturalism than on formalised blueprint adult rapidly. It is thought that ane reason for the rapid development of naturalistic course was a growing awareness of Classical remains in places where they were most numerous and a deliberate imitation of their mode. The consequence is that there are doorways which are Romanesque in form, and yet show a naturalism associated with Early Gothic sculpture.[6]

I of these is the Pórtico da Gloria dating from 1180, at Santiago de Compostela. This portal is internal and is particularly well preserved, even retaining colour on the figures and indicating the gaudy advent of much architectural ornament which is now perceived every bit monochrome. Around the doorway are figures who are integrated with the colonnettes that brand the mouldings of the doors. They are three-dimensional, but slightly flattened. They are highly individualised, not simply in appearance only besides expression and bear quite strong resemblance to those around the due north porch of the Abbey of St. Denis, dating from 1170. Beneath the tympanum at that place is a realistically carved row of figures playing a range of different and easily identifiable musical instruments.

Painting [edit]

Manuscript illumination [edit]

A number of regional schools converged in the early Romanesque illuminated manuscript: the "Aqueduct school" of England and Northern French republic was heavily influenced by late Anglo-Saxon fine art, whereas in Southern France the fashion depended more on Iberian influence, and in Deutschland and the Low Countries, Ottonian styles continued to develop, and also, forth with Byzantine styles, influenced Italy. By the twelfth century there had been reciprocal influences between all these, although naturally regional distinctiveness remained.

The typical foci of Romanesque illumination were the Bible, where each book could exist prefaced by a big historiated initial, and the Psalter, where major initials were similarly illuminated. In both cases more lavish examples might have cycles of scenes in fully illuminated pages, sometimes with several scenes per page, in compartments. The Bibles in item often had a, and might be spring into more than one volume. Examples include the St. Albans Psalter, Hunterian Psalter, Winchester Bible (the "Morgan Leaf" shown to a higher place), Fécamp Bible, Stavelot Bible, and Parc Abbey Bible. By the end of the period lay commercial workshops of artists and scribes were becoming significant, and illumination, and books generally, became more than widely available to both laity and clergy.

Wall painting [edit]

The large wall surfaces and plain, curving vaults of the Romanesque menstruum lent themselves to mural decoration. Unfortunately, many of these early on wall paintings have been destroyed by damp or the walls take been replastered and painted over. In England, France and kingdom of the netherlands such pictures were systematically destroyed or whitewashed in bouts of Reformation iconoclasm. In Denmark, in Sweden, and elsewhere many have since been restored. In Catalonia (Spain), in that location was a campaign to save such murals in the early 20th century (equally of 1907) past removing them and transferring them to safekeeping in Barcelona, resulting in the spectacular collection at the National Art Museum of Catalonia. In other countries they have suffered from state of war, neglect and irresolute style.

A archetype scheme for the full painted decoration of a church building, derived from earlier examples ofttimes in mosaic, had, every bit its focal indicate in the semi-dome of the alcove, Christ in Majesty or Christ the Redeemer enthroned within a mandorla and framed by the four winged beasts, symbols of the Four Evangelists, comparison directly with examples from the gilded covers or the illuminations of Gospel Books of the menses. If the Virgin Mary was the dedicatee of the church, she might replace Christ hither. On the apse walls below would be saints and apostles, perhaps including narrative scenes, for example of the saint to whom the church building was dedicated. On the sanctuary arch were figures of apostles, prophets or the twenty-four "elders of the Apocalypse", looking in towards a bust of Christ, or his symbol the Lamb, at the pinnacle of the arch. The north wall of the nave would contain narrative scenes from the One-time Testament, and the s wall from the New Attestation. On the rear w wall would be a Final Judgement, with an enthroned and judging Christ at the top.[nine]

1 of the most intact schemes to exist is that at Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe in France. The long butt vault of the nave provides an excellent surface for fresco, and is busy with scenes of the Old Testament, showing the Cosmos, the Fall of Man and other stories including a lively depiction of Noah's Ark consummate with a fearsome figurehead and numerous windows through which can be seen Noah and his family on the upper deck, birds on the middle deck, while on the lower are the pairs of animals. Some other scene shows with great vigour the swamping of Pharaoh's regular army by the Carmine Sea. The scheme extends to other parts of the church building, with the martyrdom of the local saints shown in the catacomb, and Apocalypse in the narthex and Christ in Majesty. The range of colours employed is limited to calorie-free blue-green, yellowish ochre, reddish brown and black. Similar paintings exist in Serbia, Spain, Germany, Italy and elsewhere in French republic.[10]

The now-dispersed paintings from Arlanza in the Province of Burgos, Spain, though from a monastery, are secular in subject-matter, showing huge and vigorous mythical beasts above a frieze in black and white with other creatures. They give a rare idea of what busy Romanesque palaces would take independent.

Other visual arts [edit]

Embroidery [edit]

Romanesque embroidery is best known from the Bayeux Tapestry, simply many more than closely worked pieces of Opus Anglicanum ("English work" – considered the finest in the West) and other styles have survived, more often than not equally church building vestments.

Stained glass [edit]

The oldest-known fragments of medieval pictorial stained glass appear to date from the 10th century. The earliest intact figures are 5 prophet windows at Augsburg, dating from the late 11th century. The figures, though potent and formalised, demonstrate considerable proficiency in design, both pictorially and in the functional use of the glass, indicating that their maker was well accepted to the medium. At Le Mans, Canterbury and Chartres Cathedrals, and Saint-Denis, a number of panels of the 12th century have survived. At Canterbury these include a figure of Adam digging, and another of his son Seth from a serial of Ancestors of Christ. Adam represents a highly naturalistic and lively portrayal, while in the effigy of Seth, the robes have been used to great decorative effect, like to the all-time stone carving of the menstruum. Drinking glass craftsmen were slower than architects to change their style, and much glass from at least the starting time part of the 13th century can be considered as substantially Romanesque. Especially fine are big figures of 1200 from Strasbourg Cathedral (some now removed to the museum) and of about 1220 from Saint Kunibert's Church in Cologne.

Most of the magnificent stained drinking glass of France, including the famous windows of Chartres, date from the 13th century. Far fewer large windows remain intact from the 12th century. One such is the Crucifixion of Poitiers, a remarkable limerick which rises through iii stages, the lowest with a quatrefoil depicting the Martyrdom of St Peter, the largest cardinal stage dominated by the crucifixion and the upper stage showing the Ascension of Christ in a mandorla. The figure of the crucified Christ is already showing the Gothic curve. The window is described by George Seddon as beingness of "unforgettable dazzler".[11] Many detached fragments are in museums, and a window at Twycross Church in England is made up of important French panels rescued from the French Revolution.[12] Glass was both expensive and fairly flexible (in that information technology could exist added to or re-bundled) and seems to have been often re-used when churches were rebuilt in the Gothic style – the earliest datable English glass, a console in York Minster from a Tree of Jesse probably of before 1154, has been recycled in this fashion.

See besides [edit]

- Romanesque architecture

- Listing of Romanesque artists

- Castilian Romanesque

Notes [edit]

- ^ Some (probably) 9th century near life-size stucco figures were discovered behind a wall in Santa Maria in Valle, Cividale del Friuli in Northern Italy relatively recently. Atroshenko and Collins p. 142

- ^ G Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. 2, 1972 (English trans from German language), Lund Humphries, London, pp. 140–142 for early on crosses, p. 145 for roods, ISBN 0-85331-324-5

- ^ V. I. Atroshenko and Judith Collins, The Origins of the Romanesque, p. 144–150, Lund Humphries, London, 1985, ISBN 0-85331-487-X

- ^ Howe, Jeffery. "Romanesque Compages (slides)". A digital archive of architecture. Boston College. Retrieved 2007-09-28 .

- ^ Helen Gardner, Art through the Ages.

- ^ a b c d e Rene Hyughe, Larousse Encyclopedia of Byzantine and Medieval Art

- ^ Roger A. Stalley, "Irish gaelic Fine art in the Romanesque and Gothic Periods". In Treasures of Irish Art 1500 B.C. to 1500 A.D., New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art/Alfred A. Knopf, 1977.

- ^ "Satan in the Groin". beyond-the-stake. Retrieved 2007-09-28 .

- ^ James Hall, A History of Ideas and Images in Italian Art, p154, 1983, John Murray, London, ISBN 0-7195-3971-iv

- ^ Rolf Toman, Romanesque, Könemann, (1997), ISBN 3-89508-447-half dozen

- ^ George Seddon in Lee, Seddon and Stephens, Stained Glass

- ^ Church website Archived 2008-07-08 at the Wayback Machine

References [edit]

- Legner, Anton (ed). Ornamenta Ecclesiae, Kunst und Künstler der Romanik. Catalogue of an exhibition in the Schnütgen Museum, Köln, 1985. iii vols.

- Conrad Rudolph, ed., A Companion to Medieval Art: Romanesque and Gothic in Northern Europe, 2d ed. (2016)

External links [edit]

- Metropolitan Museum Timeline Essay

- crsbi.ac.uk (Electronic annal of medieval British and Irish gaelic Romanesque stone sculpture)

- Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture in Great britain and Ireland

- Romanes.com Romanesque Fine art in France

- Círculo Románico: Visigothic, Mozarabic and Romanesque art's in all Europe

- Romanesque Sculpture grouping on Flickr

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Romanesque_art

0 Response to "The Age of Pilgrimages Romanesque Art What Is It Meant by the Whote Robe of Churches"

Post a Comment